Last June in Tabatinga, deep in the Amazon, an Indigenous Ticuna healer told me he had a vision of “Lula floating toward the Planalto” – Brazil’s government house. The healer, who also was a pastor of a Pentecostal church, told me that Bolsonaro was “louco” – crazy.

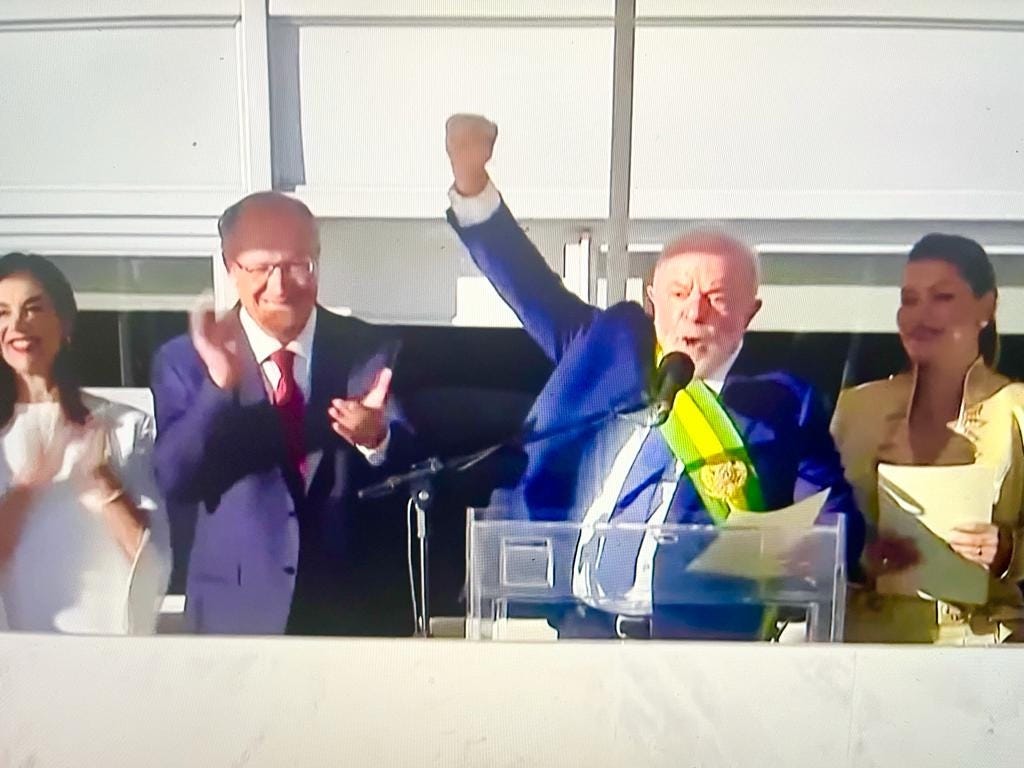

The dream of the Tabatinga healer came true when Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, known as Lula, was sworn in at the Planalto Palace in Brasilia, the capital city, on Sunday. But Lula didn’t float toward the white esplanade of the Planalto Palace. Accompanied by his wife, Rosangela da Silva, Lula walked amid heightened security after a Bolsonaro supporter was arrested for trying to detonate explosives at Brasilia’s airport on December 26.

Since his defeat in the October 30 election run-off, Bolsonaro has been doing what Trump did in the US – rabble-rousing his followers to violently disrupt the rise of the new government. For the 78 years old leftist Lula, the threats from the proto-fascist Bolsonaro and his followers will be a significant challenge for him and the shaky Brazilian democracy.

Unlike his previous two terms in office, Lula will have to lead in a substantially different and adverse context. He will govern under the small margin obtained with the defeat of Bolsonaro and with an ultraconservative right-wing parliament. He will also have to deal with the political leaders of Brazil's most potent urban enclaves, such as San Pablo, Río de Janeiro, and Minas Gerais, among others – they are all controlled by right-wing politicians.

To add insult to injury, Lula will have to rule with a government apparatus systematically infiltrated by Bolsonaro’s closest allies – the military. They have been placed in critical positions in the country’s public administration and more significant numbers than during the last dictatorship- 1964-1984.

Lula must restore civilian power over the armed forces and the police. Tackling this problem is crucial for the fate of his government and, indeed, Brazil’s democracy. Easy to say, hard to implement. Going beyond its constitutional functions, the armed forces and the police have supported Bolsonaro's regime since it arrived in Planalto Palace in 2019. Key military officers have benefited from high salaries, and a massive share of the federal budget has been destined to purchase military equipment.

In Tabatinga, in the heavily militarised Amazonian border where Colombia, Peru and Brazil meet, Lula’s ceremony attracted thousands to the long main thoroughfare – Avenida Amizade, Friendship Avenue. In Tabatinga, like in many regions of Brazil with a high indigenous population and poverty index, the support for Lula was overwhelming.

Home to around 12,000 Ticunas, one of the largest indigenous communities in Brazil, Tabatinga is part of the State of the Amazon – the state with the second-highest rate of extreme poverty in 2020.

Since his election in 2018, Bolsonaro and his economy minister, Paulo Guedes, implemented ultraliberalism that has dismantled the state’s participation in the economy. During his government, at least 20 million Brazilians have fallen below the poverty line, poverty that was reportedly eliminated under the 2003-2010 Lula government.

Under Bolsonaro, Brazilian economic growth stopped – unemployment rose, and the poverty of tens of millions of Brazilians. Lula will have to act quickly in innovating and implementing public policies to generate jobs. Once again – it will be a mighty task.

Lula’s team dealing with the transition has discovered more alarming data daily. More than holes, there are real craters in the budget allocated to 2023, the first year of Lula's new presidency, especially those planned for education, health, and the environment.

Despite all of this, Lula has the experience to turn things around. “Lula in Brazil was, despite the mistakes he undoubtedly made and will make, a competent, professional and, in good measure, a successful president during his two first terms,” wrote Mexican scholar Jorge Castañeda.

President Lula is expected to use the expertise of his first two governments with Bolsa Família – Family Allowance – a food purchase programs to handle one of the terrifying crises Brazilians are experiencing – starvation. Some 33 million Brazilians, 16% of the population, have nothing to eat, according to a survey conducted by the Brazilian Research Network on Food and Nutritional Sovereignty and Security.

In Tabatinga, the same region where British journalist Dom Phillips and the indigenous Bruno Pereira were murdered in June, Lula’s victory has become an existential prospect for indigenous people and the survival of the Amazon. In his victory speech, Lula vowed to work to achieve zero deforestation. “Brazil and the planet need a living Amazon,” he said.

When Brazilians are grieving the death of the legendary Pele and hoping for better days, Brazil needs Lula – a former trade unionist born in poverty with the dexterity required to rescue a country on the edge of an abyss. Lula only has four years.